Animal City Madness

It was late at night when the movie ended. The audience in the theater was reluctant to leave, sitting in their chairs listening to the closing song “Try Everything” and bobbing their heads to the superb rhythm. I was immersed in the same atmosphere and kept replaying the shock of the movie. This movie has elements of successful animation in recent years: the hilarity of Ice Age, the growth of How to Train Your Dragon, and the healing of The Incredible. But “Animal City” is so different again. It amuses children while making adults ponder. In just two hours, the movie not only uses the complete world view to shoot reality, but also uses the continuous reversal of the plot to challenge the audience’s ethical views, thus completely subverting the traditional Hollywood animation “silly and sweet” formula.

The “Crazy Animal City” is sure to be a big success at the box office with those funny animals alone. But what I’m more curious about is what kind of debate the movie will generate and whether it will become a classic of contemporary culture. In my opinion, the film has at least three progressive connotations that are worth noting in the movie.

1. Animal Topia

Frankly speaking, the translation of “Animal City” is not the worst among all Hollywood movies. After all, there are “The Golden Three Darters”, “Stimulus 1995”, “Food Story” and other oddities in the translation world. But “Crazy Zoo” erases the important implicit message in the English name “Zootopia”. In the English name, “zoo” means zoo, and “topia” is the Greek root word for “place”. This Greek root is often found in an English word: utopia, i.e. “utopia”. Therefore, a more accurate translation of the movie would be “Animal Topia”.

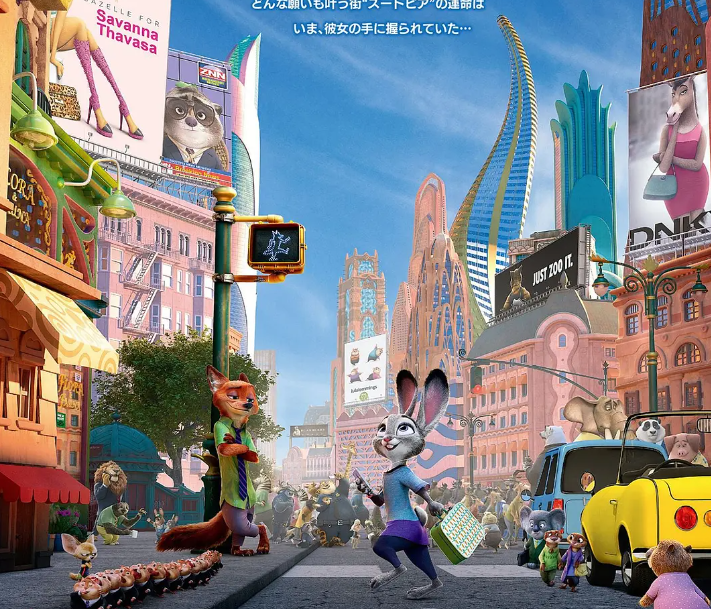

<Image 1

As a synonym for “ideal society,” “utopia” is derived from the eponymous work of the sixteenth-century English scholar Thomas Moore. In that book, Moore created an island with a perfect social system that not only abolished private ownership, but also achieved equality for all. Under the protection of the ideal system, the inhabitants of the island enjoy full freedom. The poverty and evils of the real world do not exist on this island. Just when the British people were hopeful about the popular politician Moore, he was executed by his friend Henry VIII.

After Moore’s death, his idea of an ideal society survived. A group of social practitioners decided to build their own utopia. Robert Owen, an English businessman, established an experimental commune in the United States. However, this commune, who abolished private ownership, failed after two years. Its failure is not surprising if one examines the economic basis of the commune. For two years, the commune did not produce anything substantial, relying mainly on Owen’s own property. This wealth was earned by Owen’s cotton mills in England. It can be said that the economic basis of this commune was exactly what the utopian idea opposed: employment in the factories, slavery in the cotton fields, and colonialism in international trade. The failure of the commune was inevitable from the very beginning.

In the 20th century, the “utopian” ideal was resurrected again as a reaction against capital. The Soviet Union undertook a more ambitious social experiment at the state level, replacing the market economy with a planned economy. But it was also at the height of the Soviet Union that the anti-utopian idea reared its ugly head. In “Animal Farm” by George Orwell, the same animals are used to allegorize politics. The pigs who led the revolution assumed power. As a result, new hierarchies emerged from Animal Farm, which had been moving toward the goal of equality. As predicted in Animal Farm, the Soviet administration became bureaucratized and the economy ossified. The Soviet Union eventually collapsed.

The “Animalopia” in “Animal Farm” is also an idealized city. All animals live together regardless of race, and each animal can become what it wants to be. But as the play progresses, the audience will find that the “Animal Kingdom” is only a conceptual ideal, far from reality. The first connotation of whether “Animalopia” is an encouraging “utopia” or a satirical “anti-utopia” is explored from the very beginning of the movie.

2. Adult Love Fairy Tale

Crazy Zoo” does not stop at the abstract concept of “utopia”. From the very beginning, the movie deliberately alludes to reality. In one of the most typical scenes, rabbits rush to the traffic bureau to check the license plate number, but the traffic bureau clerks are some slow-acting sloths. The children were happy to see the simple sloths on the screen, but the adult audience had a bitter smile on their faces: life’s dragging administrative processes, probably worse than the sloths. The conflict of species in the movie also corresponds to the current racial conflict in the United States. There is species prejudice everywhere in Animal City: rabbits are not suitable for police, foxes are liars, herbivores are weak, and carnivores are brutal…… Likewise, there is serious racial prejudice in the United States; presidential candidate Trump does not hide his racist attitude. It can be said that “Crazy Zoo” is a fable about reality.

Fables are called “fairy tales for adults” and often use metaphors to describe society and human nature. The Chinese classic “Journey to the West” is on the surface a story of gods and monsters, but on the inside it is also a fable. The Monkey King, independent and capable, dares to make a scene in the Heavenly Palace and overthrow the order of the Heavenly Court, which is often seen by later generations as a manifestation of the spirit of rebellion. The pig is not only lazy and cowardly, but also greedy for women, symbolizing the weakness of human nature. The indirect metaphor of the fable is like a small puzzle left to the reader to play with. For the purpose of satirizing reality, the parable is more likely to capture an audience, and its smiling satire is better than a direct attack.

But as a fable, what “Animal City” is most interested in opposing is the common facial interpretation of fables, such as the lion representing the ruler and the fox implying cunning. As the plot develops, the real character of the animals always deviates from the corresponding traditional face. The rabbit, which should be timid, is brave and warm-blooded, and the fox, which should be cunning, is kind and sincere. The small size of the animal became a gangster; the large size of the animal is a pony. The villain of the film is even more surprising. The second meaning of the film is to use allegory to interpret reality and use anti-face to oppose racism.

3. Culture changes the world

At the end of the movie, a concert is held in the animal city which is back to peace. Superstar Antelope sings “Try Everything” on stage. This song is in line with the theme of the film that the voice-over is illustrating: every animal has its flaws, but this should not be a divide between species. The only way to cross species differences is to try hard and not give up communication. With the music, different animals dance hand in hand under the stage. The iconic carnival atmosphere of Disney films finally returns in this one-night bash. The director’s choice of a culturally specific singer as the ultimate means to bridge the rift may seem far-fetched, but there is precedent.

In the 1960s, American society was divided by issues such as racial conflict, the feminist movement and the Vietnam War. At a time when the public was confused about the future, John Lennon, the lead singer of the Beatles, was directly involved in mainstream American culture as a pacifist spokesman. His song “Give Peace a Chance” was seen as an anti-war anthem. Over 100,000 students gathered in Washington, D.C., to sing in unison:

All we are saying is give peace a chance

(We are saying give peace a chance)

This anti-war movement put enormous pressure on the Nixon administration and eventually led to the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Vietnam. Lennon’s song was undoubtedly the product of a civil movement, but it in turn furthered the anti-war movement and became a case study in how soft culture changed the hard world. Lennon’s cultural power was gained through the modern means of media. The gazelle in “Animal City” is the Lennon of the animated world, representing the hope of animals across species prejudices.

Similarly, Disney’s intention in launching an allegorical “Animal City” in an American election year is not simple. America is now, as it was in the 1960s, facing a serious divisive crisis. Terrorist attacks have alienated the Arab community, and the economic recession has led to attacks on immigrants. Trump’s arrogance in the election has further terrified minorities. In such an environment, “Zootopia” with the concept of “racial integration” on the silver screen is like a fresh breeze amidst the filth. As to whether “Zootopia” can become a cultural totem that changes the world, it is the third connotation that I look forward to interpreting in the future.

Translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator (free version).